The

Sensible Supercars

CAR Magazine –

February 1987

by Gavin Green

For the price of a Testarossa you can

buy virtually all three of these supercars.

All place the engine behind the driver, and all are sensual as well as sensible

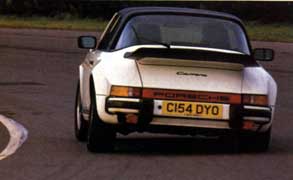

It was on a A-Road to Barnstaple, in the south-western corner of England, that the 911 proved its superiority beyond doubt. The road was tight, yet wide, and well cambered. The twin beams of the Carrera's lamps lit up the pitch black night. The only other light came from behind: the slit-eyed beams of the Renault GTA, dancing over the bumps and crests, and, further back still, the white dots I knew to be the headlamps of a Lotus Esprit Turbo. I drove hard, as did my comrades – road test editor Richard Bremner, aboard the GTA, and photographer Ian Dawson, a fine driver, in the Esprit. Yet the Lotus – visible only on the longer straights – gradually fell back. And the GTA, once a couple of strong widely spaced headlights, either side of a low-slung nose, slowly receded into the night as well. The Porsche sped on, tailor-made for this winding, sinuous A-road. There was little traffic. When a slower car appeared ahead, the Porsche loped past with the ease of a Seb Coe overtaking joggers on his morning run.

Porsche 911s come alive in these conditions. You can rush towards corners with great speed and rely on those superb brakes to wipe off the unwanted impetus. It's important to be positioned correctly, however, because they are not forgiving cars. As long as the placement is right, you'll be able to get the power down early – before the apex of the corner – and catapult out of the bend, that glorious flat-six engine growling behind you. The rear Pirelli P7s will grip – you rarely get wheelspin in the dry so good is the traction – and the 911 is on its way, engine wailing exultantly. But every corner is a challenge when you're driving a 911 hard. Other cars may allow you the luxury of effortless high speed performance, but not this one. As we've said often enough before – most recently, in the last month's Top Ten– the 911 is a car that involves you with an intimacy that few machines can equal. The steering is never dead: it moves slightly even in the straight-ahead, as the wide P7s roll over the tarmac, and is very sharp when the car's moving at speed. Throttle response is instantaneous: ask of that engine and you will receive; the car will jerk impatiently forward, like a racehorse. Back off and the car baulks.

The sheer wieldiness of the 911 was an important aspect of its superiority on that winding A-road in north Devon. Porsches are little cars, in ways that Lotus Esprits and Renault GTAs are not. The passenger door is barely more than a stretch away from the driver. The twin front wings that end in the headlights, are not long: in short, there's not much in front of you. There's not much behind either, as you are reminded by the proximity of the trailing edge of the whaletail spoiler – very nearly the rear of the car.

The 911 did not pull away easily on that Devon road – that would be to exaggerate the measure of its superiority. But pull away it inexorably did. 'I just couldn't keep up. That 911 is very fast.' said Bremner. Dawson looked the most exhausted. His countenance was as eloquent as his words. 'This car's hard work if you want to drive quickly,' he said, nodding at the Lotus. I, too was tired because great concentration had been needed. Yet worthwhile rewards are won only when some effort has been called for. And no car, I believe, could have covered that A-road more quickly, or involved its driver so pleasurably, as did the 911. That's what I like about them. And that's why 911s are still the greatest of the mid-range sensible supercars.

The Renault (Alpine) GTA Turbo was the car that most made us doubt the 911's supremacy. It has the same flawed layout as the Porsche – its engine hangs out over its rear axle – yet it is mated to turbo V6 power, full wishbone suspension and a set of clothes which must be the most stylish to adorn any sports car in years (and the most aerodynamic _ the Cd is 0.30). Alpine – a wholly-owned Renault subsidiary – is no Jean-come-lately in sports car terms, either. The company has been building rear-engined performance machines for more than 30 years – almost as long as Porsche. It learnt, a long time ago, how to overcome the major engineering inadequacies of a rear-engined design. A number of world rally championship victories, with the excellent little A110, are evidence of that. Further to add to the new Alpine's appeal, its British pricetag – £23,635 (in turbo form) – undercuts the base 911 by around £9000. If you add the wings and the wide P7s to the Porsche (and most customers do), the gap jumps to £11,451, as the 911's price rises to £35,086. There is no premium for the Targa model, as tested. Price lists may suggest that the GTA is aiming for the jugulars of the 944S or Audi Quattro. Yet, despite the price disparity, the Renault people are unequivocal about the car they'd most like to beat with their new plastic fantastic. On the road it's the 911 they are after.

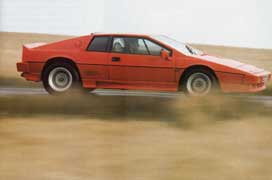

The GTA is also chasing the finest British car in the 'sensible' supercar category. The Lotus Esprit Turbo may be getting old – although, at six, it's a mere stripling compared with the 911 – and its wedge shaped flat-sided styling really is a hangover from the '70s. Age has not lessened its greatness, though. It has much in common with the newer GTA: glassfibre body over a sturdy metal backbone chassis, turbo engine (although, in the Lotus's case, it's placed amidships not out the back) and largely hand construction by a small manufacturer. It's directly price-competitive with the French car, too. At £24,980, the Turbo Esprit has never looked such a bargain. Not so long ago, it was more expensive than the base 911 (instead of being almost £8000 cheaper), and wasn't that much cheaper than a Ferrari GTB (which now costs £14,000 more!). Mind you, Porsche and Ferrari have been especially greedy these past few years.

Our comparison test began in London. Sports cars, of course, are not designed to perform well in town, yet as with dogs in houses, they are nevertheless expected to behave themselves there. In the city, the 911 was slightly superior – by dint of its compact dimensions and good visibility, and because of the ease with which you can see its corners. Parking can be done by sight, not by touch. You'll need to give the clutch pedal and the steering wheel far more than a touch when you're manoeuvring into a parking position, though – both are firm and require the sort of effort many would not want to expend in everyday driving.

But it's not a difficult car to drive, nor is there a great feeling of occasion when you get behind the wheel. The interior is simply too prosaic for that. The dash is plasticky, and not attractive. The switchgear – especially those little rocker switches littered over the dash – is cheap, and would be derisive if part of an Escort GL package, let alone that of a £30,000 sports car. Porsche has had 23 years to sort out the ergonomics. The fact that it is still disgraceful suggests an unhealthy indifference to customers' needs. The seats look cheap, do not hold the driver or passenger well in quick motoring, and are not particularly comfortable. The off-set pedals – owing to front wheel arch intrusion – force a skewed driving position, and the unbelievably ugly plastic centre console looks as though it has been stuck in by some plebeian owner, rather than by Porsche 'craftsmen'. Unlike most pukka sports cars, the 911 does have rear seats – which are useful for small children or luggage. The front boot is reasonably large, if shallow. It's the best of the bunch here.

As a town car, the Renault runs the 911 pretty close. Forward vision is good and, for a car which has its engine behind the driver, rear visibility is not too bad – although some guesswork is necessary when you're reversing. Good points in town include a surprisingly light clutch and nicely weighted steering: only at parking speeds is any heaving necessary. The GTA also has a good gearchange, in contrast to the rather vague and notchy shift of the Porsche. Its stop-go-steer controls are not much different from those of a normal Escort/Sierra-type car.

Its dash is not much different from the saloon car norm, either. The instrumentation is not particularly extensive, nor does the facia look expensive: it could just as easily be out of a Renault 5 as a £20,000-plus Renault sports car. Switchgear is all mainstream Renault. The dash of the GTA may not impress, but the rest of the interior does look special: beautifully upholstered seats, quality carpets and rear seats in which a couple of adults could spend an hour or so without too much discomfort.

The Lotus is a terrible companion for a night on the town. Rear vision is appalling, especially to the rear flanks. As a result lane changing and reverse parking involve as much crossing of the fingers as good judgement. Front vision is not that great, either, owing to the low seating position. If you're a six-footer, like me, your nose will be pointing straight at the steering wheel boss. The wheel itself feels high: you almost have to reach up to grab it. Yet this inordinately low driving position is part of the magic of Turbo Esprit driving. The Lotus feels different from the road car norm, in a way that neither the 911 nor the GTA does. You don't so much climb onto the seat as fall into the gap between the sill and the centre console, and repose on flash looking (but in fact rather uncomfortable) seats. The steering wheel has a chunky rim, and is of tiny diameter. White on black gauges stare at you from every corner of the facia.

But the sense of occasion – the feeling that you're in something special – is there. The adrenaline flow that a Turbo Esprit's driving environment fosters is all very well: but once the heartbeat slows down, the anger is likely to build up – at least in town. This is an excruciatingly awkward car to drive in any city. The firmness of the steering, the clutch and the gearchange don't help. Neither does the lack of carrying space: the boot, at the rear of the car rather than being in the nose (as is the case with the two back-engined machines), is small. At least it's covered in carpet, rather than in packing crate protection-like plastic (as is the case with the GTA). Surprisingly, this boot is also larger than the GTA's.

In the rush for the keys, it was the Lotus's set we'd invariably grasp last if city driving was in prospect. Sports cars never inspire affection in town. Only on the open road are the passions engaged. So we headed west. The Esprit's position as the least practical day-to-day car was further reinforced by its performance on the M4. The speed is there, all right, but it is accompanied by masses of every known type of noise motorways can engender. Wind noise, much over 80, is terrible: the wide Goodyear NCTs howl furiously as the miles are covered: the engine noise – not especially pleasant at constant throttle openings, being rather buzzy – permeates the cabin. Long trips in the Lotus are tiring. Atrocious ventilation – no new car on sale today could have worse – doesn't help. And neither do the uncomfortable seats.

The Renault and the Porsche don't quite reach saloon levels of comfort and quietness on the wide three-laners, but they don't miss by much. Wind noise levels are low; so is the mechanical intrusion (one of the advantages of having the engine stranded at the back, in no man's land). The only noticeable impediment to a relaxing journey is the tyre noise: wide low profile rubber (P7s in the case of the 911, newer P700s on the GTA) always stir up trouble on motorways. The GTA has more road noise, a corollary its particularly wide boots (255/45s at the rear), yet has slightly less wind noise than the Porsche. It also scores as the most comfortable car in which to do across-Britain trips, owing to its good seats and supple ride. A 911, or an Esprit, is firmer. Later, when side winds started buffeting the cars at speed, we found that the Alpine was easily the most susceptible. It would than start to wag its tail. The big rear tyres, acting like twin rudders, provided enough self-centring to quell any serious danger, though.

We arrived at Castle Combe, the racing circuit near Chippenham where we test the mettle of the fast cars than come our way, early that morning, after the drive from London. It was grey and cold and bleak, as it normally is at the Combe outside summer. Ahead of us lay almost two miles of fast track, with crests and brows and quick kinks and a few slowish corners; behind us, in the case of the Porsche, lay one of the finest sports car engines that has ever turned a set of back wheels. We expected this car to be the quickest of the trio. It was. Its best lap was 1 min 16.5 sec – not bad for a standard road car. That's 0.7sec quicker than the quickest lap the Renault managed. The Esprit, hindered by fuel starvation on fast corners (although there was no shortage of petrol in the tank), failed to better 1 min 18.8 sec. Although the Porsche's margin of superiority over the GTA was not great in terms of time, it felt rather more in terms of sheer speed competence. The German car was the more entertaining on the circuit, and the tidier. The 911 felt sharp, responsive, manoeuvrable. The engine revs beautifully, and has wonderful power progression. There are no flat spots, or periods of unexpected docility. Turn-in is terrific. The brakes are in another class from the Renault's or the Lotus's. Naturally, some prudence is necessary. You don't rush into corners with this Porsche. Use the brakes to wipe off the speed, enter the corner quickly – but not foolishly so – and get the power on early. That's the secret of quick 911 laps. When you get it right, the Porsche darts out of turns with amazing ferocity, and grip. Only when accelerating hard, after a slowish corner, does the steering fail to convey properly the messages being fed to it from the front wheels: that's because the nose gets light under savage acceleration. Otherwise, the response to be had from the 911's steering is superb. The gearing is right at speed; so is the weighting. The Porsche feels tailor-made for the track, in as much as any road car ever can. There is a degree of nervousness, and you know you're on the knife edge when really pressing on. But the satisfaction is there.

The GTA has enough grunt to do the job. Once on boost, the French car always feels fast – although its engine never has quite the alacrity of the Porsche's. That 0.7 sec lap time difference, though, is more a result of wayward high speed handling. The Renault just doesn't have the neatness of the 911, on the track. Its turn-in is significantly worse – the GTA has considerably more understeer and front-end scrub, when pushed, its turbo engine does its handling balance no favours, either. It is not a particularly refined turbo engine, in terms of lag. Although never less than smooth, and possessed of good low-down urge when off-boost (a result of the large capacity), the engine has a turbo that comes in some time after, you've passed on the message that you'd be liking more poke, thanks very much. And when the boost does come in, it does so with an almighty wallop. Go into a corner on boost, and the car understeers quite badly. Bring the turbo into play during the corner, and the tail can start to run wide. Such occurrences are unlikely to happen on the public road, because the speeds are unlikely ever to get that high. On private circuits, though, be warned. Another lesson came through loud and clear as a result of those Castle Combe laps; the Renault's brakes really aren't up to sustained hard work. They never felt strong.

The Lotus was a bit of an oddity at the circuit. Its times were hampered by the fuel surge – although the guess was that it still would not have been as quick as the GTA, let alone the Porsche. It rolls less than either rear-engined car, and has sharper turn-in. The brakes, which suffered from terrible vibrations when you really stomped hard on the pedal, offer acceptable retardation, but nothing like the strength of the 911's. The good thing about the Esprit, on the circuit, is its responsiveness. This car reacts very quickly to the steering – faster, even, than does the 911 – and it has good throttle response, too, owing to the almost lag-free nature of its fine four-cylinder turbo engine. The Lotus can also be thrown into corners, at speed, with more abandon than can the rear-engined machines; it's a quicker car, around corners, as a result. For all that, the Lotus is not an easy car to drive fast, or even a very enjoyable car. The steering, even a speed, is heavy – you have to work at the wheel. And, although the steering is sharp, it lacks the feedback of the Porsche's system: you somehow feel isolated from the action in the Lotus, in a way that you don't in the Porsche. There's a deadness about the steering, despite its accuracy. The appalling view out of the car doesn't help; it makes the Esprit difficult to place accurately in corners. It's twitchy, too. Whereas the Renault feels stable, but rather lifeless, and the Porsche feels sharp and nimble (if a little untrustworthy), the Lotus always feels nervous, and slightly ill-at-ease. The 911 is a considerably better track car, as its competition record indicates. We spun the Lotus. Going into a corner hard, the car got slightly crossed up – and, despite correction, it snapped quickly. The firmness of the car's suspension and its lack of suppleness, mean that the chassis of the car is not terribly communicative when things get slightly out of hand. Mid-engined cars, like rear-engined ones, are not renowned for their forgiving natures when things go wrong.

The 911's lap time advantage around Castle Combe was not only a factor of its greater suitability for circuit work; it has more straight-line grunt than its rivals, too. With 231bhp (and roughly similar weight: it's 67lb heavier than the Alpine and 155lb more than the Lotus), the 3.2 litre Porsche enjoys a 21bhp advantage over the 2.2 litre turbo Lotus, and 31bhp over the 2.5 turbo GTA, its torque spread is also the best of the bunch; the engine is strong at almost any revs. The Renault has more low and mid-range punch than the Lotus in practical terms, although the British car has more at high revs. All this means the Porsche enjoys the best 0-60mph sprint time (at 5.4 sec, it compares with the Lotus's 5.8 and the GTA's 6.1) and the best 0-100 time, too (14.1 sec, beating the Lotus by 1.5 sec and the GTA by 2.1 sec). The 911 is quickest in top speed: at 153mph, it beats the more aerodynamic Renault (150mph) and the Esprit (143mph).

With Castle Combe behind us, and the Porsche opening an all-round advantage, we headed further west, into the setting sun. It was on the winding roads of Exmoor – ideal conditions for sports cars – that most was revealed. A case can be made for all three cars, on the sinuous A- and B-roads that criss-cross the moors and are generally free from traffic. The Renault is the easiest car to drive fast – no mean feat. It feels secure on the road, and is the least nervous of the three when going hard. It's a car that can be driven, at nine-tenths, for long periods. Over a three-or four-hour drive, on tricky roads, it will probably emerge as the fastest – simply because it taxes its driver the least. The lightness of the controls, the visibility, the quietness, the comfort – there's almost a well-sorted, relaxing sports saloon feel to the GTA in such conditions. Tail wagging is never a problem. High gearing further helps the relaxed, long striding gait of this car.

Yet there are times when the Renault doesn't feel like a sports car. No such allegation can be levelled at the Esprit. It always feels different from your Golf GTI or Escort RS Turbo or Ford Capri 2.8i. Apart from the extreme lowness of the driving position, the lack of rear vision and the go-kart sharpness of the steering, there is the short throw gearchange (quite unlike that of any other road car). The change will seem awkward at first – it is very firm, and needs percision – yet, with practice, you can snatch gears in an Turbo Esprit with amazing speed. There's no need for the engine to go off-boost during the cog swaps, which cannot be said for the GTA. The noise the Esprit's engine generates could also come only from a sports car. It's a frenetic scream at high revs, and a sharp-edged buzz even in the mid-range. Back off and the wastegate flutters noisily, as it dumps the turbo's boost. Sometimes, the engine spits flames. All the sounds are there to entertain you.

On the winding roads of Exmoor – we had two full days there to play with the cars – the Esprit was always invigorating. Its sharpness. The engine response. The grip. Yet it never proved as pleasurable as the Porsche. It doesn't have the nimbleness, or the smallness. It always feels a wide car – which it is – and bulk is always a nuisance when you're trying to stomp along. The engine, although good for a turbo, doesn't react with the immediacy of Porsche's air-cooled six. And it does not provide the same usable power as does the Renault's engine, with its beefier mid-range urge. Then there are other things about the Esprit which would get on our wick after a while. The tacky finish – the leather was starting to peel off the dashboard in places. Those big unsightly panel gaps. The cheap switchgear and catches – much of the old British Leyland fitments (the interior door catches, for instance, are off the Austin 1800; the air vents are from the Allegro Series 3). There's still a kit car feeling about the Lotus, and a feeling of fragility that would worry us, were we to fork out £25,000.

The Porsche wins this comparison because the rewards that come from driving it well are so great. It's a long way from being the perfect sports car. It can be slippery in the wet – put the power down early coming out of a corner, after there has been some rain – and the car will fishtail alarmingly. Its dynamic faults, owing to its quirky rear-engined layout, are well chronicled – especially its propensity to swap ends if you back off in mid-corner. Many are the people who hate 911s – with some justification – for their tendency to be mendacious. Yet the enjoyment this car can deliver, for me anyway, outweights its dynamic vices. The pleasure also outweights the appalling dash layout. And when you get down to more mundane considerations, such as resale value, build quality, mechanical and body longevity and so forth, you not only come away with the impression that the 911 is a better car than the GTA or the Esprit in absolute terms, but that it's undoubtedly worth a higher price tag. Mind you, with Porsche's recent penchant for large price hikes, the gap between the 911 and the second best 'sensible' supercar, the GTA, is starting to get disproportionately high. The Porsche may be the most satisfying car to drive, but the GTA is the best value for money.