The

Le Mans racers you can drive on the road

Lotus Sport 300

v

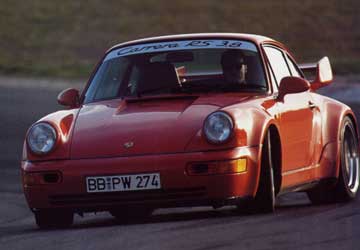

Porsche Carrera RS 3.8

CAR– July

1993

The Esprit and the 911

are wonderful road cars, and they've been developed into brilliant track

cars.

Now these racers have been let loose on the road. We drive them to the Nürburgring,

the toughest circuit in the world, where Roger Bell laps them up.

At two and a half miles a minute, this is the easy bit. On the long, wide straight that rushes the old Nürburgring back to the sanitised new, the Lotus is reeling in a 944 Turbo and a Carrera 2. Seconds later, it's hard on the mightly brakes, through a confusing wiggle and back to the pay-booth, where a peak-capped red-face is issuing speeding tickets on the nice sort to more nutters. It costs 14DM (about £5.70) for each 14 mile lap of the 'Ring'. After 28DM's worth, I need to stop for breath.

Thanks to the Carrera's driver, who know his way over the blind brows that make the old circuit so daunting to newcomers, my second lap is more or less on the right lines, if nowhere near the Lotus' limits. Just as well, perhaps. Race-bred though it is, the Sport 300's suspension is not stiff enough to cope with the 'Ring's belly-scraping dips and two tight, banked corners. Around the notorious Karussel, the body is firmly centrifuged onto the bump stops. The gear ratios are not ideal, either; long straight apart, the 'Ring is a two-gear circuit in the Lotus, despite all its crazy dips and turns; second is too low, fifth too high.

While I take a breather, editor Gillies is putting to good use his 'Ring craft, garnered the hard way in historic racers. The Porsche Carrera RS 3.8 he is driving has long since disappeared, power-sliding to order here, tucking in there with feathered understeer, always communication its attitude and intentions with a tactile intensity that makes it feel safer to hustle near the limit than the Lotus, even though it's physically more demanding. From a standing start, Gillies turns in a lap of 8min 49sec in the Porsche – a time he subsequently fails to match in the Lotus. A win for the German? Not so fast. There is more to this duel than virtuosity around the world's most demanding track. Much More.

The plan was simple enough. Photographer Tim Andrew and I would drive the latest (and best) limited-edition Lotus from Blighty to the Nürburgring via the Dover-Calais ferry. There we'd rendezvous with the RS 3.8 driven by Gillies from Porsche's Weissach R&D centre near Stuttgart. The shoot-out between these 170mph mavericks would be the highlight of an indulgent orgy of raw-power motoring.

Both cars have come full circle, from road sports to track titans back to the street as thinly veiled racers. The Sport 300 is a civilised version of the X180R Esprits that have excelled in North American SCCA and IMSA racing (last year's drivers' champ was Lotus-mounted). True, the hastily prepared, Chamberlain-run Le Mans cars were off the pace (at 185mph) and ill equipped for 24-hour survival (both failed to finish), but that takes nothing away from the Esprit's string of successes elsewhere. The RS 3.8 – three-point-eight litres, I ask you – is effectively a roadgoing version of the RSR 3.6 which qualifies for the ADAC GT Cup, 24-hour races at Spa, Le Mans and the Nürburgring, and various national GT championships, including the American IMSA series where it has been out-pacing the Lotuses but not always out-lasting them.

Such competition-bred thoroughbreds are right up CAR's high-performance street. If they are not the progenitors of future rivals, then GT racing, set for a big comeback, will not be doing its job as a breeding ground for driving machines high in adrenalin stimulation.

The Sport 300's torsionally reinforced galvanised backbone chassis carries a heavily reworked lightweight bodyshell of revised composite spec. You might miss the additional cross-bracing and bonded-in roof panel but not the textbook wheel-arch extensions that accommodate gorgeous three-piece OZ alloy wheels and whopping tyres, or the brake-cooling ducts drilled into the new, rubber-lipped front air-dam (surprisingly, the rear ducts are as falso on the Sport 300 as they are on the S4). The most striking visual feature of the macho makeover, in which several Lotus luminaries had a hand, is the 959-shaped rear wing which obliterates the view aft as effectively as a blacked-out mirror. Whatever is does for track times, on the road it's pretty daft. Springs, dampers and bushes have been stiffened, the geometrically revised suspension, adjustale at the back, hung from modified mounts, the hub carriers revised. The big ABS-equipped assisted disc brakes, clamped by four-pistion AP racing calipers, come from the X180R. Modifications to the 2174cc engine – a hybrid T3/T4 turbo, larger inlet valves, hand finished ports, recalibrated engine management – lifts power from the S4's 264bhp to a claimed 302bhp at 6400rpm (ie 139bhp per litre. Wow!). Torque is also up, from 261lb ft to 287lb ft, though it peaks higher, to the detriment of mid-range pick-up.

In its quest for lightness, Lotus has denied the Sport 300 under-carpet sound deadening, a transmission console, map pockets, speakers, even a clock. Whatever this saves – Lotus talks of 175lb – is negated on the test car, number 008 (for Bond's successor?) in a run of 50, by air-conditioning that costs £1495 extra (and is worth every penny) and a £445 Clarion radio/cassette. With its optional Pearl Yellow hue – a wacky car deserves a wacky £1995 paint job, don't you think? – the Sport 300 carries a £68,930 sticker price. Ridiculous? Not when compared with the Carrera RS 3.8, which costs DM225,000 (£91,000) in Germany. For the more powerful full-race RSR, Porsche asks a cool £110,000.

Sport 300 has fabulous balance, grip, steering: unlike most mid-engined cars, it's faithful on limit. Modified Lotus turobcharged four-banger now gives 302bhp and 287lb ft.

Porsche's tail can be wagged under power, but lift-off behaviour can be tricky. Steering heavy but communicative. Famous flat-six air-cooled engine now out to 3.8 litres, giving 300bhp and 260lb ft.

Displacement of the RS's dry-sump engine is increased from 3.6 to 3.8 litres (how much bigger can this venerable flat-six get?) by widening the bores from 100mm to 102mm. Though larger in diameter, the pistons are lighter. So are the rocker arms. Other changes include new Motronic control of the ignition and injection, cleaner gas flow from the intake to exhaust, and a dual oil cooler. Power goes up from the normal Carrera 3.6's 250bhp at 6100rpm, to 300bhp at 6500rpm – virtually the same output as the Lotus's, and 50bhp short of the RSR's – and the rev limit has been raised to 7100rpm. Torque is up from 224lb ft to 260lb ft, which is a match for the Esprit S4's but not the Sport 300's.

Out goes the Carrera's power steering, in come stiffer springs, dampers and roll-bars. Bigger tyres, too, mounted on three-piece Porsche Speedline alloys, quite breathtaking in their engineering beauty. Even so, the Lotus Esprit squats on wider rubber, its 315/35 rear Goodyear Eagles dwarfing the Porsche's 285/35 Dunlops. Revised aerodynamic aids – a front chin spoiler and a huge multi-position rear wing – are said to exert genuine downforce rather than just reduce lift. Drastic weigh-paring measures on the manual-everything Porsche include aluminium doors and boot-lid, thinner glass, deleted rear seats and a utilitarian cabin bereft of powered windows, locks and seats. Of plush trim, too: the door handles are taped loops protruding from screwed-on panels. Porsche claims a dry kerb weight of 2513lb. At 2880lb, the better-equipped Lotus is significantly heavier.

Cars approaching Wipperman bend on old Nürburgring.However you look at it, the startling Esprit is visually the more dramatic car, the one the Germans flocked around to admire. Mind you, given that Porsche are two-a-pfenning at the Nürburgring, that's not so surprising. It eclipses the stark RS for cabin opulence, too: Lotus could do a lot worse than adopt the Sport's lovely, non-reflecting suede and damask trim for the S4. It looks terrific, creates the right ambience, suits the car. Its Lotus-made bum-pincher competition seats, though, are difficult to access, particularly on the driver's side where the wide sill, low steering wheel and obstructive up-your-trousers handbrake (albeit a fly-off one than can be laid flat) hinder entry. Getting into the Porsche's Recaros is much easier: the door gap is wider, the sills narrower, the wheel much higher, the cabin more spacious. What's more, the RS's lovely stitched-leather seats are better padded to avert the numb-bum syndrome that the Lotus driver suffers after a couple of hours behind the small Nardi wheel. More buttock cushioning would not go amiss. Ditto more under-thigh support.

The dashing Lotus is not at its best on the sprint east along French and Belgian autoroutes At 100mph, engine boom nurtures a headache. Not that you can hear much of the four-cylinder twin-cam's harsh, hard-edged cacophony above appalling coarse-surlace tyre roar. Only on super-smooth roads at even higher speeds – engine noise subsides at 120mph – is it possible to appreciate the Lotus's hushed arrowhead wind penetration. There must e many miles of smooth autobahn in Germany where the Lotus will cruise without cranial discomfort at 130mph. On brushed and bumpy Belgian concrete, though, it is an aural assailant.

We leave the autoroute at Malmedy for a couple of tentative laps of the famous Spa-Francorchamps circuit. The first is on the fabulous new track, the GP drivers' favourite, the second on the terrifying old. I was there, in the '60s, when two British aces – Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey – were killed in separate incidents in the same race, and Moss and Taylor badly injured. Burnenville, the Masta kink (actually a flat-out S-bend), Stavelot . . . these were the corners of heros, not men. Jackie Stewart's safety crusade was triggered by a rare crash at Spa, where the grandstands and pits sill line what most of the year is a public road.

The Lotus might have been made for the cross-country dash from Spa to the Nürburgring. German secondaries – the smoothest in the world – suit a suspension set-up that by road standards, if not track ones, is as solid as set concrete. Elsewhere, the harsh and agitated ride had crucified my coccyx. Here in the Eifels, spinal discomfort gives way to emotional uplift as the two Gs – grip and grunt – command our attention and approbation. Road cars do not corner or handle better than the Sport 300, exotica's yardstick by a metric furlong. Steering is wonderfully precise and linear: you're aware of neither understeer nor oversteer, just a go-where-you-point-it neutrality. Roadholding is prodigious, while the car's ability to change direction like a fleeing gazelle is a revelation on twisty roads. Hard cornering's usual tell-tales – body lean, tyre squeal, front-end plough, slip angles – are notable by their absence. All you sense here in the Lotus is intimate feedback through the suede-rimmed steering wheel, and huge lateral g heaving against your hips and shoulders: the seat's awkward torso-hugging side-pieces may be a hurdle to negotiate but they certainly clamp you down when zapping through bends.

To be caught off boost in the Lotus is to be caught languishing. The engine is flexible enough low down but lacking in potency until the tacho needle swings towards 4000rpm. There's no sudden kick, just a tidal wave of torque which burgeons with unbridled brawn all the way to seven-two cut-out. Traction is terrific, even in the wet, Lotus's patented new limited-slip diff – a compact cluster of planet gears and suns – working with unobtrusive brilliance. Overtaking is ferociously brief, short straights are despatched in a fleeting frenzy. If anything disappoints, it's not so much the engine's peaky delivery as the cosmic gaps in the Alpine Renault gearbox. The Sport 300 would be all the better for a close-ratio gearset to go with its uprated clutch and new LSD. And a six- for eight-cylinder engine, of course, if only to generate superior sound effects. Lotus's sloper-four may be a giant killing technological marvel, but after a cold start it clatters with the metallic decorum of a cement mixer – of a Jaguar XJ220, indeed.

How different the wailing Porsche, which excites and enthrals as soon as you fire its glorious flat-six engine, and blip the razor-sharp throttle – wang, wang. Despite a superior power-to-weight ratio, all-out performance is very similar to that of the Lotus: from rest to 60mph in both cars takes a tyre smoking 4.6 sec, to 100mph less than 12. Porsche claims a top speed of 168mph, Lotus 169mph. Taken to the limit, a brace of more evenly matched rivals would be hard to find. It is in character and voice, not in speed, that these two slingshots fundamentally differ. For a start, the RS 3.8's huge muscle is more accessible. It lunges at low revs where the Lotus lingers; it thumps you in the back while its rival's lag-prone turbocharger pump is still gathering momentum unless you've blipped the revs and dropped a gear. What the Porsche won't do, mind, is ample cleanly on a light throttle; here the Lotus has the smoother, more refined delivery. Despite the noisy clatter of idler gears, the RS also has the sweeter gearbox, its ratios better matched to the engine's power and torque curves, its short-throw lever looser, more precise. Not that shifting is anything but an entertaining indulgence in the Lotus, too.

The rim of the Porsche's big, high-set wheel is as thick as a coiled python, all the better to grasp and control. You steer from the shoulders, arms aloft, not with the wrists, as in the assisted Lotus. If the man-machine intimacy imparted by the Esprit is subtle, it's close to overwhelming in the RS, which draws you into action through steering that writhes and kicks incessantly. Without numbing power assistance, every nuance of the chassis's behaviour is communicated, easily assimilated. After the Lotus – ultra-sensitive but never nervy – the Porsche feels heavy, almost unwieldy; hampered by a wretchedly large turning circle, it is unwieldy on manoeuvres. Whereas you can flick the Lotus through corners wristily, elbows lazily cradled by both rests, the Porsche needs encouraging into them, even forcing, against strong self-centring feedback that carries an unequivocal message: understeer.

In indycar jargon, the RS 3.8 is a pushy car on the road, not a loose one. Like the Lotus, it betrays its race-biased suspension with a thunking, gut-jarring ride on anything but table-smooth surfaces. On the track, where the limits of adhesion are more easily explored and breached, you quickly discover that the RS 3.8 is a power-sensitive as the Lotus is throttle-benign. In the British car, directional control is down to steering. You brake, point and squirt, in the classic mid-engined manner. In the German car, line adjustments are made as much with a feathered right foot as with blurred hands. The pendulum effect of the outrigger engine is there all right, but it's under firm control and can be used to advantage to generate power oversteer. Accomplished though the Lotus is when driven fast on the road, to throw it around the 'Ring' with as much abandon as you can the Porsche would be to push your luck. My guess is that the Esprit's cornering powers comfortably exceed those of the RS. Trouble is, you need to know the car intimately, and the track even better, fully to exploit them. Two laps are not enough.

Mightly anchors are taken for granted. If those of the Lotus have greater arresting powers, the Porsche's feel more progressive and reassuring when extended. Both cars have welcome off-clutch rests to brace against. Surprisingly, the pedals of neither car are perfectly aligned for fancy heel-and-toe footwork. More space between throttle and brake would not go amiss in the Lotus, and the RS would be better – as would all 911s – for pedals that didn't sprout from the floor.

By and large, the Porsche is the more practical, despite earbashing wind noise at autobahn speeds. For a start, it's roomier, with space for in-cabin luggage, though the Esprit's two boots are in combination quite decent. You get a better view out the the slim-pillared Porsche, more generously glazed than the Lotus. Moreover, the rear wing doesn't obliterate the mirror view aft. Neither car has very classy instruments: three of the Lotus's supplementaries are masked by the wheel rim, and the Porsche's look passé. Both have seatbelt buckle's that jab your elbows. While the RS's cabin is starkly functional, the Lotus's simple plushness is a roadgoing bonus.

At the end of the three-day thrash, there is not real winner. The Porsche has the better engine and gearbox, the Lotus the more accomplished chassis. On the track, the RS 3.8 was faster, more relaxing; on the road, the Esprit stole the show dynamically, though not aurally. Now, what about putting that wailing flat-six in the back of the Lotus. . . ? No harm in dreaming.

It's all in the rules

The Le Mans racers you can drive on the roadFISA has neglected sports-car racing. Yet touring cars are drawing crowds all over Europe.

Why, asks Mark Gillies, can't sports cars do the same?Wouldn't you just love to go to a race where you could actually buy all the cars on the track? And where they weren't just high-tech single-seaters that only the brilliantly talented could drive, but beautiful, sonorous GT cars that would be equally at home – with some mild de-tuning – on the road?

Some will deride attempts to market racing for road cars, but look at the success of Europe's touring car championships. Big crowds watch cars that appear to be versions of their own Vauxhall Cavaliers and Ford Mondeos battling it out on the track. Look at the success of NASCAR stockers in the US. Again, the cars outwardly resemble Ford Thunderbirds and Chevy Luminas, even if their underpinnings are very different.

Who's to say that these success stories couldn't be repeated with sports cars? Over the years, the quality of sportcar racing has deteriorated from wheel-to-wheel racing between machines that looked something like road cars, to dull parades of what were effectively rebodied Formula Once machines.

Most people would say that the heyday of sports-car racing was pre-'71, when monstrous 5.0-litre Group 4 GTs such as the Ferrari 512 and the Porsche 917 ruled the roost. In truth, these cars were little more than specialised road racers, although they were built in batches of 25 and could in theory be used on the road. And, in fac, the leader boards of sports-car events had been dominated since the mid '50s by racing cars that could be used on the road, rather than by road cars modified for racing.

It was always the GT class that was most relevant to you or me. In the early '60s, Jaguar's Lightweight E-type, AC's Cobra, Aston Martain's DB4 GT and Zagato, Bizzarrini's A3/C and Ferrari's 250 SWB, 250GTO and 275GTB/C were all competition versions of road cars that could be bought and driven on the public highway. All were beautiful, better-handling and significantly faster versions of production cars, and all are highly desirable today. In long-distance events, GTs frequently did will, humbling faster but more fragile prototypes: at Le Mans in 1962, for instance, a GTO finished second. By 1966, though, new regs had effectively done for the GT racing car.

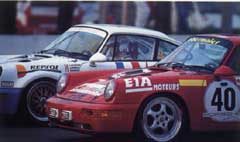

GT Class at 1993 Le Mans allowed entries from modified road cars. Jaguar XJ220c (centre) won, but was disqualified on a technicality,

while Lotus Esprit didn't last (left). Porsche 911s in wheel-to-wheel formation (right).It has been proposed that the future of sports-car racing lies with GT cars, which currently race in a number of different series and events around the world. First, there's the Le Mans 24-Hours, which this year had class for GT cars: among the entries were a Jaguar XJ220, a Porsche 911 Turbo, a few Venturis and a couple of Lotus Esprit Sport 300s. There are also national championships in Germany, Holland and Italy, where (mainly) weathly amateurs race Porsches, Ferraris, Hondas and their ilk. And IMSA in the US runs a series for production supercars in which, in 1992, Porsche took the manufacterers' title, and Lotus the drivers' title.

There's been much posturing on all sides of late, because the sport's governing body, FISA, has been trying to write a set of homogeneous rules for a world championship. However, FISA doesn't seem to care about anything but Formula One, and has yet to finalise a calendar for the GT series. Worse still, the rules are flawed.

FISA has proposed a list of suitable cars which are 'on genuine and general sale to the public and have been registered for road use in at least two of the following countries: France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Germany, Japan, USA, Italy and Britain.' In a two-class championship, 'at least 25 identical cars must have been produced' to compete in Class One, so that manufacturers can come up with homologation specials. In Class Two, the cars must also be homologated in FISA's Group B, for which at least 200 examples must have been produced (although the manufacturers involved would like to see that figure lowered to 50, to allow makers such as Marcos and TVR to join in).

Modifications are relatively limited, with a minimum weight of 1100kg for all but four-wheel-drive machines, which carry a 150kg penalty. The mandatory fitment of air-restrictors on both turbo and normally aspirated cars limits power to 500 bhp in Class One, and 350bhp in Class Two. Maximum wheel-rim width is 14in, and wheel-arches must be no more than 10cm wider than standard. The flaw in the rules concerns weight. A 1350kg limit had originally been agreed: the new FISA proposals would penalise makers such as Lamborghini and Bugatti.

If the rules can be adjusted, we should see a revitalisation of sports-car racing, involving Porsche, McLaren, Lamborghini, Bugatti, Jaguar, Venturi, Lotus and Ferrrari. There ought to be factory and supported teams fighting it out at the front, with privateers joining in at the back.

I'd like to see GT racing promoted properly. And I'd like to see FISA acknowledge that there's life outside formula one, and that racing can further the road-car breed. The Sport 300 and Carrera RS 3.8 demonstrate that car manufacturers can produce wonderful machinery off the back of racing: I'd just like to see more cars of their ilk.